Much of Como was ‘Whites Only’

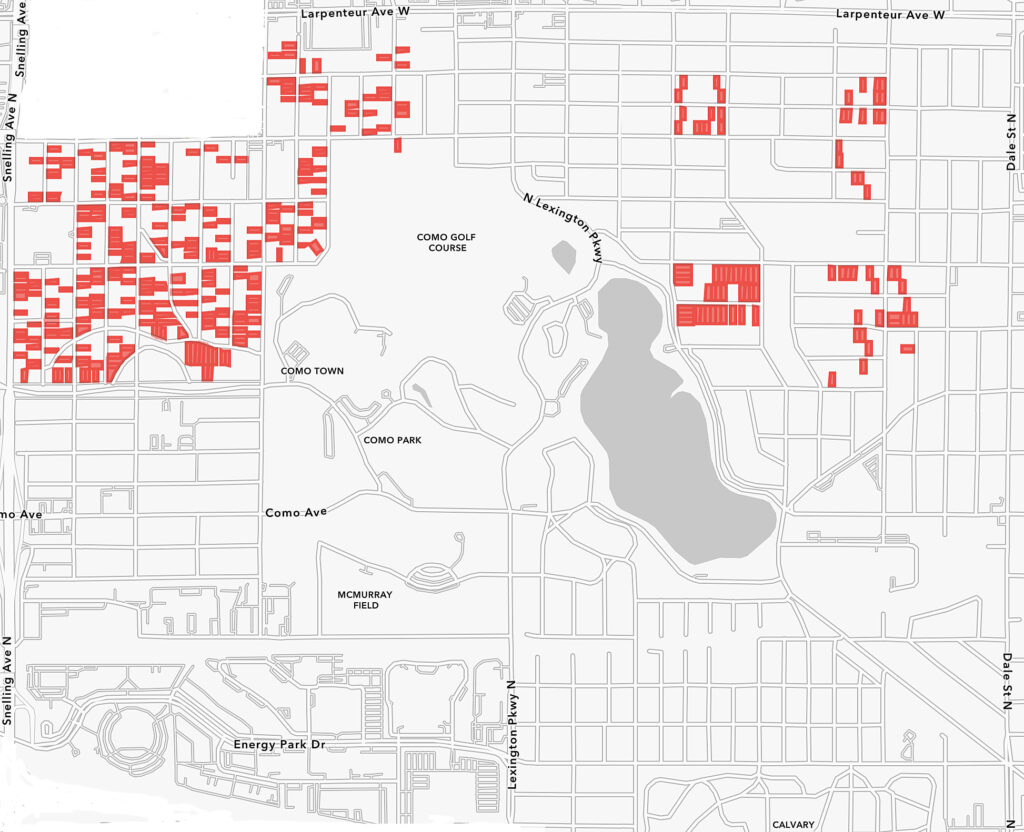

At least 350 homes in Como contain racially restrictive covenants, new research by the University of Minnesota’s Mapping Prejudice project shows. The covenants created impenetrable barriers; for decades, they meant only white people could own those homes or live in those parts of the neighborhood.

Racial covenants were a “system of American apartheid,” Mapping Prejudice says. Though covenants now are unenforceable, their language remains on property deeds to this day – and their impact has never gone away, says Kristen Delegard, director and co-founder of the project. The covenants’ legacy, she says:

- continues to shape neighborhood segregation, exclusivity, and amenities

- is embedded in a range of private and public housing policies and decisions, such as redlining and low-density zoning

- contributes to massive housing, wealth, and generational inequities between whites and people of color, especially black Americans

A definition of structural racism

Racially restrictive covenants were common in the Twin Cities from 1910 through World War II. That helps explain where they are most common in Como. On Mapping Prejudice’s preliminary maps for Ramsey County, covenants show up in red – like a rash in well-delineated parts of Como. (For a more-detailed look, click on the map above, or download the PDF)

Delegard calls racial covenants a classic example of structural racism. Their result: huge swaths of land in Minneapolis and Saint Paul reserved exclusively for white people. Officially, that included more than 8 percent of Como’s single-family homes. It does not count any spillover impacts from living next door to or near properties with covenants.

The private real-estate contracts that contained covenants didn’t always use the same language, but they achieved their goals in similar ways. A covenant from early in the 20th century said: “… the premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.”

Other covenants, instead of listing “objectionable” people, made it plainly clear the property was for whites only. One version stated: “… the said land or buildings thereon shall never be rented, leased or sold, transferred or conveyed to, nor shall same be occupied exclusively by person or persons other than of the Caucasian Race.” Another version took a similar approach, using a different description of white – and making it clear that black servants were OK: “No persons of any race other than the Aryan race shall use or occupy any building or any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race domiciled with an owner or tenant.”

Covenants are clustered

In Como, it is not always the grandest homes – the ones that might have kept servants – that have covenants. More typically, it is the common, sometimes modest homes built before and between the World Wars. As Mapping Prejudice’s map shows, there are substantial swaths where covenants are common. East of the lake, there areas are:

- Between Hoyt, Milton, Idaho, and Victoria

- Between Idaho, Grotto, Nebraska and Avon

- Between Arlington, Alameda, Ivy, and Avon

- Between Arlington, Victoria, the south side of Parkview, and Milton

West of the park, covenants are even more prevalent. Between Midway Parkway and Hoyt, nearly every block has covenants; on many of these blocks, covenants are the rule rather than the exception. It is similar slightly farther north – between Hamline, Larpenteur, Fernwood, and Hoyt. The notable exceptions: the institutional blocks that now hold Humphrey Job Corps Center, Chelsea Heights Elementary School, and Northwest Como Recreation Center.

An open secret

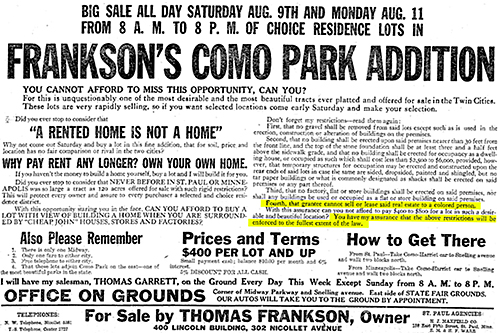

The frequency of covenants west of Como Regional Park is attributable in large part to one-time Lt. Gov. Thomas Frankson. While developing “Frankson’s Como Park Addition,” he ran huge newspaper ads boasting that “the grantee cannot sell or lease said real estate to a colored person” and that the restrictions would be “enforced to the fullest extent of the law.”

Mapping Prejudice points to Frankson’s ad as a prime example that racially restrictive covenants were anything but secret. They were well-publicized and overwhelmingly popular among white people, Delegard says, because there were seen as protecting neighborhoods and protecting property values. (Ironically, Mapping Prejudice did not find a racial covenant on Frankson’s iconic mansion at the corner of Hamline and Midway.)

In 1924, research shows, the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ Code of Ethics barred agents from “introducing into a neighborhood … members of any race or nationality … whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values.”

These private contracts, promoted by developers and real estate agents, worked hand in hand with a series of other public and private practices, Delegard says: a history of seizing land from indigenous people; redlining by bankers, city planners, and elected officials; and blatant harassment, intimidation, threats of lynching, and outright violence and mob action carried out by everyday white people to keep their neighborhoods white.

The U.S. Supreme Court made racial covenants unenforceable in 1948, the Minnesota Legislature made new covenants illegal in 1953, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 made covenants illegal nationally. Since then, there has been “white amnesia,” Delegard says. “We find that many people are shocked by these racial covenants.”

Consequences are evident today

But black people continued to see them for what they were, she said: the infringement of individual rights, a system built to keep black and brown people contained to certain areas, and a legal means to restrict them from owning property and amassing wealth elsewhere. The consequences are evident a century later.

In Minneapolis, houses that had covenants have values 15 percent above the median; houses in redlined communities are worth 25 percent less than the median, Mapping Prejudice research shows. In white communities, Delegard says, grandparents and parents were able to build and pass along wealth from owning homes. That helped their children buy homes, which solidifies generational economic security, she says; families of color rarely had those opportunities.

Now, the Twin Cities have the largest home ownership gap between white and black families in the country. One manifestation: In Saint Paul, 83 percent of Black residents rent, said Kayla Schuchman, of the city’s Department of Planning and Economic Development, compared with 41 percent of white residents. .

Housing sits at the foundation of other disparities, Delegard says, including vast differences in health, educational access, and everyday amenities. A visible example: Majority white neighborhoods tend to have more parks and more generous tree cover. Communities of color, on the other hand, have more environmental hazards such as landfills and highways, Mapping Prejudice says.

Research in Ramsey County continues

Volunteers spent more than 20,000 hours over the past year helping Mapping Prejudice examine 49,604 property deeds in Ramsey County. The project is still building the kinds of maps and information on this side of the river that will be interactive, similar to what was first done in Minneapolis and Hennepin County. Delegard expects the patterns of segregation, property values, and inequities will be similar, too.

During a preview look on April 8, Ramsey County Commissioner Trista Matas Castillo noted: “The inequities were created intentionally; we will have to work just as intentionally to make amends.”

Mayor Melvin Carter made a similar point. He instructed the Saint Paul city attorney’s office to work with the nonprofit Just Deeds “to provide the legal services necessary to dismantle covenants where we find them.” The City Council authorized that partnership on April 21, to help property owners “discharge” covenants on their property if they want to.

“It’s not just enough to say we are no longer enforcing them,” Carter said. “We have to literally erase them from the books and undo the consequences.”

However, neither the city nor Just Deeds has yet provided details on how that might work, and how individual property owners can uncover and act on covenants that may linger on their deeds.

Copyright 2021 Como Community Council. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License